ERC Grant for Paweł Nowakowski Ph.D.

We are happy to announce that Dr. Paweł Nowakowski is among the laureates of prestigious grants from the European Research Council (ERC). The researcher was awarded with a Starting Grant in the humanities and will lead the project entitled “Masters of the stone: The stonecutters’ workshops and the rise of the late antique epigraphical cultures (third – fifth century AD)” acronym: STONE-MASTERS. The grant amounts to almost 1.5 million EUR.

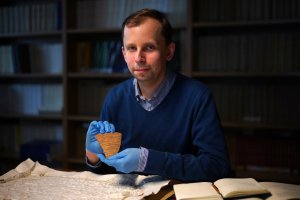

Dr. Paweł Nowakowski will examine the changes in the culture of commemoration at the close of the Roman Imperial period, and the influence which craftsmen, stonecutters who made inscriptions on stelae, buildings or tombstones, had on them.

The aim of the research is to explain one of the most startling problems in the global history of research on the collective memory and the practice of commemoration, i.e. the transformation of the epigraphic traditions of the early Roman Empire, which began in the mid-third century and resulted in the rise of the so-called epigraphic cultures of Late Antiquity.

The conclusions will allow us to see in a new light the role of commonly available prefabricated goods, modelled on the changing objects of the elitist culture, in the broadly understood cultural change, and their producers – craftsmen, as the basic agents of vertical cultural transfer, adapting the culture of the elite to the needs of the middle and lower echelons of the society.

How do societies shape the memory of themselves?

During the Roman Empire, inscriptions, usually commemorating the lives or achievements of individual people, the construction of public buildings, or other events important for local communities, became a ubiquitous element of the landscape of cities, smaller centres or roadside cemeteries. It is even said that a penchant for inscriptions became one of the correlative elements of the Roman “cultural package” and one of the main determinants of “being Roman”.

However, in the third century C.E., this beautiful and old tradition which provided us with so many valuable sources for the social history of the Empire, was transformed. In some provinces, the number of inscriptions fell to a fraction of the previous number, elsewhere their shape, form, decorations, lettering used, and finally the circumstances of their commissioning completely changed. The ancient art of epigraphic commemoration was resurrected only by the Renaissance antiquarians and collectors, laying the foundations for the modern European epigraphic commemoration, traces of which we encounter all around us in today’s world.

Engaging debates about this transformation have been going on continuously since at least the 1980s, when the problem was fully noticed and defined, and when we realized its importance for the history of cultural memory. So far, however, no consent has been reached with regard to the reconstruction of its causes, course and effects. Historians observe the phenomenon, consider various explanations, but it still remains a mystery to us. There is certainly more to it than a simple correlation with the political and military crisis of the Roman Empire in the third century.

Stone masters

Dr. Nowakowski claims that the transformation could have been driven by a refreshed understanding of the role of epigraphy and its forms in the middle and lower social strata. Stonecutters’ workshops dealing with the production of prefabricated inscriptions could be responsible for this. If so, then only an in-depth understanding of these environments can provide us with an understanding of the processes underpinning the entire transformation.

Today we have no doubt that in many regions it was stonecutters who advised average buyers – women and men, what form of inscription should be chosen from a limited dossier of ready-made shapes of plaques, decorations or dedicatory formulas, e.g. to commemorate a dear cousin, deceased wife or successful completion of construction. Some of such “product catalogues” (i.e. collections of formulas placed on commemorative plaques or on lintels of houses) have survived even in the form of manuscripts.

If it happened that the stonecutters simultaneously carried out special orders for the local aristocracy, they learned about the aristocrats’ taste in the culture of commemoration and trends in the elitist culture. They could then draw inspiration from them for their repertoire of inscriptions, offered to less wealthy buyers. Thus, they became a vital element of the vertical (“top-to-bottom”) cultural transfer, and at the same time a kind of a cultural filter, adjusting the high culture of the elite to the tastes of an ordinary buyer.

We can guess that the changes that have occurred in the culture of the elite, among others in connection with the removal of the senators from provincial administration and the command of military units, the spread of Christianity and the following “ostentatious humility”, changes in the culture of civic competition (agonistic culture) and other phenomena, influenced in very different ways the shape of inscriptions commemorating someone’s achievements. The disappearance of old, well-established career paths naturally had to lead to the emergence of new models of career descriptions, or even new models of civic virtue. Stonecutters, modelling their catalogues of products, made these novelties spread wider and wider, and probably did the same with generalized ways of thinking about what is worth commemorating and how to talk about their own and other people’s lives. As a result, the change reached people who have never had anything in common with the great state career or with foundations of magnificent buildings.

Explaining changes

This approach requires new research instruments. Researchers of epigraphy of the Roman Empire still have a small number of instruments at their disposal, allowing them to learn about the workshops involved in the production of inscriptions. In part, this is due to the fact that their attention was mainly drawn to other research strands: quantitative epigraphy (epigraphic curves), research on the self-presentation of people or groups displaying inscriptions, the visibility of inscriptions in the urban landscape or the “visual studies” and “culture of viewing”, very popular in recent years.

Meanwhile, Dr. Nowakowski intends to create a team which will develop the “Digital Atlas of Workshops in Epigraphy” – an advanced digital instrument for collecting the data on emerging and disappearing styles of decorations and lettering, stonemasons’ marks (ancient “logotypes” of workshops), signatures of stonecutters, stone trade routes, quarries active in Late Antiquity or any other markers, allowing the identification of both larger and smaller workshops dealing with the production of inscriptions.

The next phase of the project will be the construction of regional networks of workshops that will allow us to observe changing styles and environments which favoured them. An inspiration will surely be a careful adaptation of the workshop study methods developed for other crafts and periods – in particular for Greek vase painters of the archaic and classical period, and for the scribes and their scriptoria, whom we safely identify today as important “cultural mediators”.

The direction of work proposed by Dr. Nowakowski has a chance to redirect the attention of the entire community of researchers of ancient inscriptions from recipients and commissioners to the makers of the inscriptions – craftsmen and their workshops – as the basic agents of vertical cultural transfer.

We can expect a significant increase in our knowledge of epigraphy as a cultural phenomenon, especially in the middle and lower strata, for use in the study of any epigraphic culture where professionals producing inscriptions are present. And finally, perhaps we will get an answer to the question of whether such transformations in the memory of societies can repeat themselves.

See also Information on the home page of the University of Warsaw and www page

Researcher profile

Dr Paweł Nowakowski is an assistant professor at the Department of Ancient History of the Faculty of History of the University of Warsaw and a member of CRAC UW (the Centre for Research on Ancient Civilizations, established last year as part of the Excellence Initiative, Research University).

The current grant is not his first experience with the ERC – between 2015 and 2018 he was a postdoc research associate at the University of Oxford, on the ERC Advanced Grant “The Cult of Saints in Late Antiquity”. In addition, Dr. Nowakowski was the PI of the project financed by an NCN Preludium grant in 2013–2015, and currently leads the team project “Epigraphy and Identity in the Early Byzantine Middle East” funded by an NCN Sonata grant (2020–2023). He was also a laureate of the “Start 2013” scholarship of the Foundation for Polish Science, the scholarship of the Minister of Science and Higher Education for outstanding young researchers (2020–2023) and the Krupp Stiftung scholarship at the University of Cologne (2011).

As a publisher of new epigraphic finds, he cooperated with the mission of Princeton University in Avkat / Beyözü (Turkey) and the mission of the Faculty of Archaeology of the University of Warsaw in the quarries of Göktepe (Turkey – Marmora Asiatica project, NCN Sonata Bis grant held by Dr. Dagmara Wielgosz-Rondolino).

The ERC STONE-MASTERS project will be based at the Faculty of History of the University of Warsaw. It is the first independent ERC grant obtained by the Faculty. Previously, the Historical Institute was a partner in the ERC Advanced Grant “The Cult of Saints in Late Antiquity” (Host Institution: Oxford University), where the Warsaw team was managed by prof. Robert Wiśniewski.

About ERC grants

The European Research Council is an independent EU agency established in 2007 by the European Commission, financing top-quality research conducted in the European Union. The board is managed by the Scientific Council, which consists of eminent European scientists.

Prestigious ERC grants finance pioneering, ground-breaking research conducted in any scientific field. “High risk – high gain” is the motto of ERC grants, for which the only criterion for evaluation is scientific excellence. Grants are awarded to academically active people who can, demonstrate significant achievements in the last decade, adequately to the field represented and their own career path.

From its foundation until 2020, the ERC awarded 19 grants to scientists from the University of Warsaw (in Poland, it was a total of 41 grants). Grants for 2021 will increase the number of university grant recipients with three outstanding people: an employee of our Faculty, Dr. Paweł Nowakowski, Dr. Dorota Skowron from the Astronomical Observatory and Dr. Michał Tomza from the Faculty of Physics, University of Warsaw.

In this year’s edition of ERC grants, out of over 4,000 applications, 397 projects were awarded, for a total amount of EUR 619 million. The winners represent research institutions from 22 countries. Eight projects were financed in Poland (including 3 from the University of Warsaw).

In total, the University of Warsaw has acquired (until 2021 inclusive) 22 ERC grants: 14 in the Starting Grants category, 5 in the Consolidator Grants category, 2 in the Advanced Grants category and 1 in the Proof of Concept category.

Photo: Mirosław Kaźmierczak